All webfooted wanderers stumble sooner or later, and that’s when the trouble begins. So here’s a guide to getting up and moving on after your snowshoes have let you down.

______________________________

by Tamia Nelson | February 15, 2019

Originally published in different form on March 5, 2013

Snowshoeing has long been our favorite mode of winter travel, and we’re not alone in this. Snowshoes make it easy to break free from the groomed trails that attract droves of skiers (not to mention packs of snowmobilers), allowing the modest plodder to strike out cross-country more or less at will. After all, there really isn’t any terrain that snowshoes can’t handle, though snowshoers, like all winter wanderers, are well advised to exercise extreme care when crossing frozen lakes and streams, and the most prudent course is to avoid such crossings altogether.

Once safely off thin ice, there are few, if any, insurmountable barriers. Steep, forested slopes that are off-limits to skiers pose no problems for experienced big-footed travelers, and while snowmobiles wallow and sink helplessly in deep powder—most snow machines are now engineered to race along groomed trails at 70+ mph, while their nature-loving riders rejoice in the hydrocarbon-enriched fresh air whipping past their discreetly masked faces—the huffing and puffing snowshoer shuffles cheerfully through the enfolding drifts, doing her best not to look smug.

Ah, yes. The huffing and puffing snowshoer. There’s no denying that snowshoeing can be hard work. Still, there are many of us who don’t mind investing a little sweat equity to reap a recreational dividend. And there’s a growing consensus that—within reason, at any rate—strenuous exercise is good for all ages and conditions of men and women. But I don’t have to make the case for working up a sweat to you, do I? It’s what we do for fun. Which isn’t to say that the snowshoer won’t welcome a little assistance from time to time, and this help is readily available, in the form of cross-country ski poles and basket-equipped trekking poles. Not only do poles give you a boost under way—they allow your arms to share the work of motoring through those trackless drifts—but they also provide vital props when negotiating tricky terrain. A 180-degree turn in place can be a bit of a struggle for the bipedal novice, but with a pair of ski poles converting her into a confident quadruped, the maneuver is easy. Well, easier, anyway.

What about you? Are you a veteran webfooted backcountry explorer, or are you only now preparing to take your first steps? If you’re just stepping out, so to speak, you’ll learn to walk in snowshoes mostly by strapping them on and walking. It’s a little like being a toddler again. And that’s the rub. If you remember learning to walk—I don’t, I’m afraid, but I’ve received reliable reports—you probably remember falling. A lot. This happens to novice snowshoers, too. And that’s

The Downside of Snowshoeing

Don’t think you’re exempt. It’s bound to happen. Even old hands take a tumble now and again, and beginners often fall several times in their first hour. The falling itself isn’t usually a problem. Unlike a hapless skier, falling free after catching an edge on a black diamond run, you probably won’t hit a tree at 30 mph. (I did this once. I don’t recommend it.) Unless there’s a rock or the stub of a beaver-gnawn sapling lurking just below the snow surface, your fall will probably be more like a comfortable collapse onto a feather bed than anything else. The problem comes afterward, when you try to get up. And the deeper and fluffier the snow, the bigger the problem.

Given that falling is inevitable and that getting up after a fall can be anything from awkward to (almost) impossible, why hasn’t more been written about this necessary skill? Why, indeed. Well, I’m going to do something about that right now. Herewith, then, is a short primer on

How to Get Up After Falling Down

OK. You’re down. Your assignment is to get back on your feet, quickly and easily. But I won’t make it easy for you. If hard cases make bad law, as has often been asserted, they make for good examples. Anything that works when everything is against you will work even better when fortune smiles. So I’ll assume the worst when I set the scene. The snow into which you’ve fallen is fathomless powder, far deeper than your ski poles are long. There are no trees or sturdy branches within reach. And you’re alone. In short, getting up is going to be up to you. (I will assume that you’re uninjured, however, and that, while you’re neither a gymnast nor a contortionist, you suffer from no particular physical limitations.)

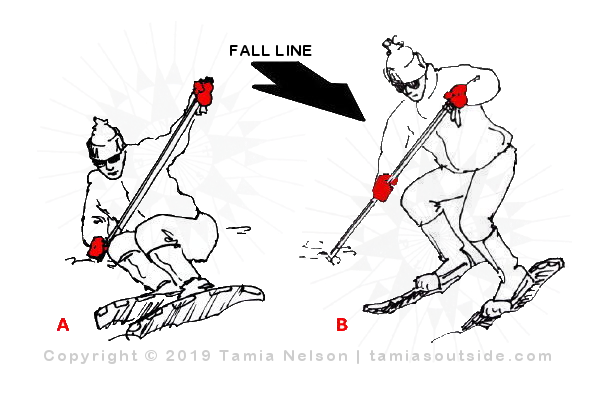

What next? Use your poles. And here I’m going to give you one further advantage: Your poles have wide “powder” baskets, not the skimpy little butterfly wings intended for skiers who stay in a rut. These are the best—I’d say the only—choice for snowshoers who venture off the beaten track. And here’s how to put them to work for you when you’re down on your luck:

Simply flounder around till your snowshoes are lying parallel on the downhill side—this is easy with short aluminum-frame bearpaws, but it’s quite a job with long Ojibwa-pattern shoes—then take your hands out of the wrist loops, gather your poles together, plant the baskets on the uphill side, and push (A in the sketch above). Now “climb” the poles till you’re on your feet again (B). (The upper hand stays put. The lower hand does the climbing.) If you’re on flat ground, that’s all there is to it. On a slope, however, you’ll want to get your head uphill, with your snowshoes arrayed below you, perpendicular to the fall line, before you start your pole climb.

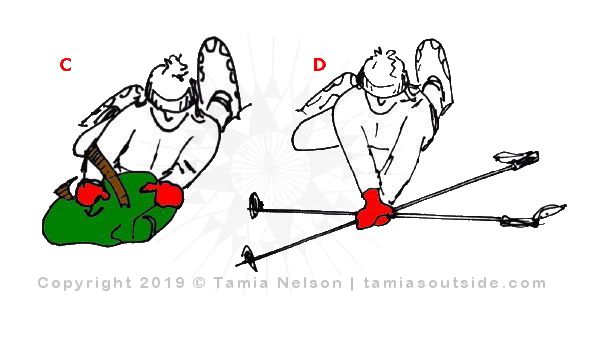

No luck? Then your baskets are too small (or the snow is a really feathery powder.) You’re in no position to go shopping for new baskets, and you probably can’t afford to wait for the snowpack to firm up, so you’ll have try Plan er CD. If you’re wearing a pack—and you should be if you’re walking in winter—you can remove it and use it as a support (C in the sketch below). In fact, removing your pack can make recovering from a fall easier under almost any circumstances, especially if the pack is large, awkward, or heavy. Be careful on steep slopes, however. Packs have a disconcerting way of becoming toboggans, and it’s really demoralizing to see all your carefully chosen gear slide away into the distance. (This, too, has happened to me. I don’t intend to repeat the mistake.)

If, on the other hand, your pack is too small or too limp to be of much use as a platform, give the Treasure Island technique a go. On all good treasure maps, X marks the spot. So cross your poles, grab hold of them at the join (D in the sketch above), and use them as a support while you get your feet (and your snowshoes) under you. Once you’ve done that, rise from your squat, steadying yourself with the poles—now held as they were in the earlier sketch (A). It’s not always easy, but it can be done.

There are, of course, many variations on these basic themes. And the best way to master them is to practice them. Climbers practice ice-ax arrests. Paddlers practice wet exits, recovery rolls, and canoe-over-canoe rescues. Snowshoers, too, can benefit from practicing self-rescue techniques. Just pick a time (and a place) where the penalty for failure is low. Ask a level-headed friend to come with you, ideally with a warming hut or lean-to nearby, and make sure there’s plenty of cocoa in the thermos. It also pays to wear waterproof pants.

What are you waiting for? Go play in the snow while you still can. Spring will be here before we know it!